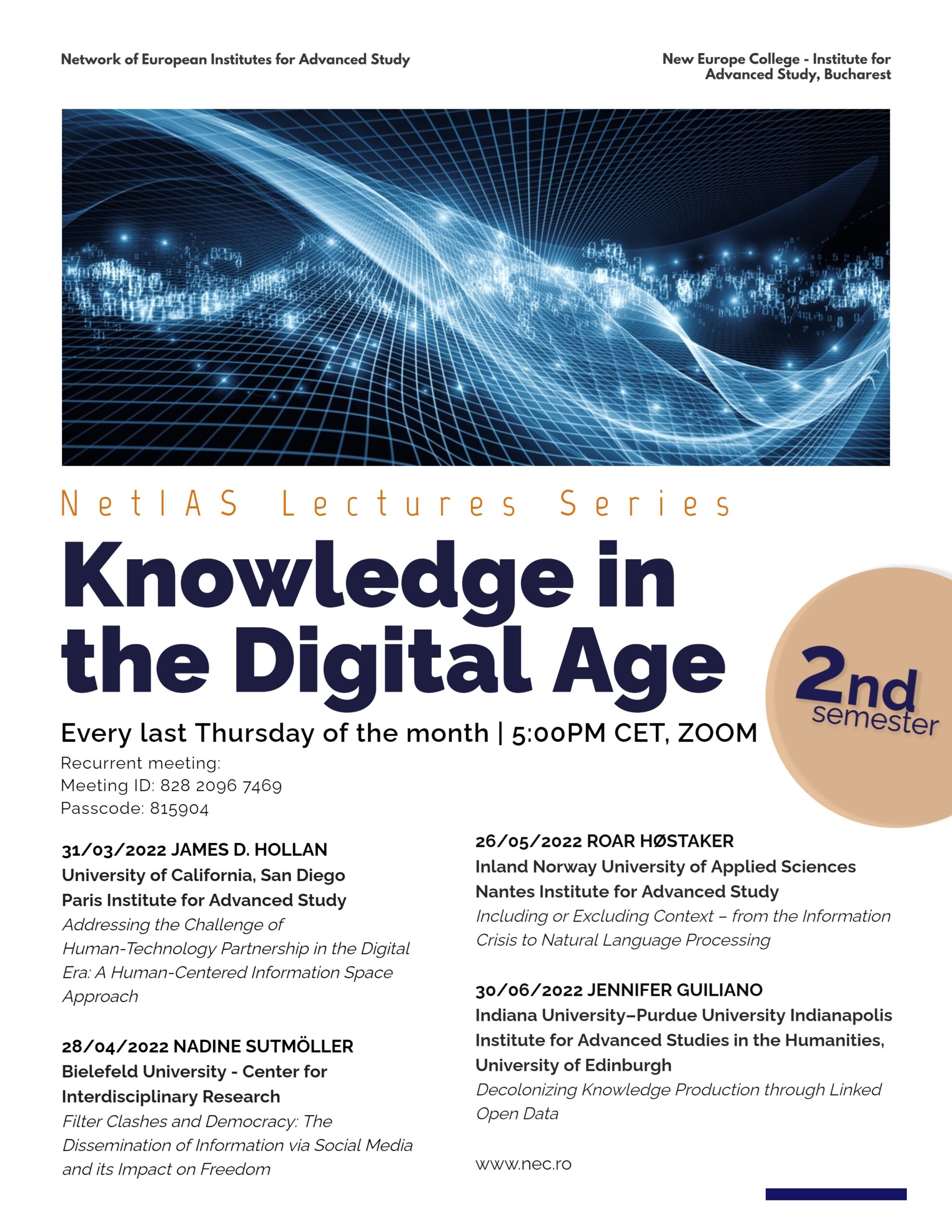

European NetIAS Lectures Series: Knowledge in the Digital Age, every last Thursday of the month, at 5 PM (CET), via Zoom [Second Semester]

28 February 2022

The series Knowledge in the Digital Age continues in the second academic semester with thought-provoking lectures, followed by Q&A sessions.

The spring program includes some fascinating forays into cognitive science (James D. Hollan, Paris Institute for Advanced Study), social networks (Nadine Sutmöller, Center for Interdisciplinary Research-Bielefeld University), Natural Language Processing – NLP (Roar Høstaker, Nantes Institute for Advanced Study) and a perspective on Indigenous digital humanities and history (Jennifer Guiliano, Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities – University of Edinburgh).

The conferences in the Knowledge in the Digital Age series are organized by New Europe College in collaboration with NetIAS (Network of European Institutes for Advanced Study).

For the events held in the first semester of the academic year click here.

The login details below are valid for every lecture:

Recurrent meeting:

https://us02web.zoom.us/j/82820967469?pwd=RVV0NDJoTXBoMEN0YktqeDd4SFE0QT09

Meeting ID: 828 2096 7469

Passcode: 815904

Program of the spring semester:

March 2022

31/03 JAMES D. HOLLAN

University of California, San Diego

Paris Institute for Advanced Study

Addressing the Challenge of Human-Technology Partnership in the Digital Era: A Human-Centered Information Space Approach

April 2022

28/04 NADINE SUTMÖLLER

Bielefeld University – Center for Interdisciplinary Research

Filter Clashes and Democracy: The Dissemination of Information via Social Media and its Impact on Freedom

May 2022

26/05 ROAR HØSTAKER

Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences

Nantes Institute for Advanced Study

Including or Excluding Context – from the Information Crisis to Natural Language Processing

June 2022

30/06 JENNIFER GUILIANO

Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis

Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities, University of Edinburgh

Decolonizing Knowledge Production through Linked Open Data

Short abstracts

31/03 JAMES D. HOLLAN

Professor of Cognitive Science and Computer Science, University of California, San Diego

2021/2022 Fellow, Paris Institute for Advanced Study

Addressing the Challenge of Human-Technology Partnership in the Digital Era: A Human-Centered Information Space Approach*

“The computer desktop was an amazing design for its time, but does not reflect the complexity, flexibility, and sociality of human activity…Eventually we will have to reorganize the desktop to reflect the complex mix of activities users engage in and move beyond the rigidity of separate applications and files-and-folders.” – Bonnie Nardi, Acting with Technology: Activity Theory and Interaction Design, 2009.

For far too long we have conceived of thinking as something that happens exclusively in the head. Thinking happens in the world as well as the head. We think with things, with our bodies, with marks on surfaces, and with other people. Increasingly, we think with computers, often the one we carry with us everywhere. Computers are now ubiquitous and embedded in virtually every new device and system, ranging from the omnipresent cellphone to the complex web of socio-technical systems that pervade and shape modern life. They connect our activities to ever-expanding information resources with previously unimaginable computational power. Yet with all the increases in capacity, speed, and connectivity, computer-mediated information activities remain fragmented and frustrating. Designing the future of work at the human-technology frontier is one of the ten long-term science and engineering challenges identified by the U.S. National Science Foundation. In this presentation, I argue that a core aspect of this challenge arises from an unquestioned view of information systems as collections of separate passive tools rather than active partners. The scale of information available and the sophisticated cognition demanded by contemporary information work has outpaced innovation in user interfaces. In modern computing systems, information is encapsulated in silos, leaving users to shuttle files between applications, cobbling together workflows, requiring troublesome context switching and increasing attentional demands. In short, we lack a human-centered information work space, a cognitively supportive visual space for intellectual work.

A human-centered information space is both an idea, and a computational environment. It is the idea of a spatial cognitive workspace—a desktop for intellectual activity—reified as a computational environment that actively supports the coordination of information activities. It should develop awareness of the history and structure of a user’s action: how she accomplishes activities through discrete tasks across devices, programs, and working sessions. Through use, each representation in the linked computational environment accumulates structure and context: not only who accessed it and when, but relationships to concurrent and other semantically related information and activities. This context and history of activity should drive the behavior of information representations. To the user, her information should seem alive, have awareness, know where it came from, how it got there, what it means—and behave accordingly. These dynamic representations will in turn guide the user’s future action, providing a supportive personalized information context. It is important to emphasize that the human-centered information space will not replace the user’s ecosystem of documents and applications, but be a separate space linked to them, acting as a home, a control center, a multi-modal but fundamentally ‘spatial workshop’ where information across applications will converge augmented with visual features and active behaviors to support the user in not only completing her tasks, but accomplishing long-term overarching activities.

________________________

*This presentation benefitted from a FIAS fellowship at the Paris Institute for Advanced Study (France). It has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 945408, and from the French State programme “Investissements d’avenir”, managed by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-11-LABX-0027-01 Labex RFIEA+).

28/04 NADINE SUTMÖLLER

Postdoctoral Researcher, Center for Interdisciplinary Research, Bielefeld University

Coordinator, Research Group Economic and Legal Challenges in the Advent of Smart Products

Filter Clashes and Democracy: The Dissemination of Information via Social Media and its Impact on Freedom

Media and, increasingly, social media play a key role in democratic societies by disseminating information. However, the new instruments and their dynamics are fundamentally changing this game: As often explained the new media are characterized in particular by the algorithmically controlled curation of content based on collected data. To avoid information overload, the filtering approach makes perfect sense. However, at the same time, this procedure raises questions that strike at the heart of a democratically ordered society: What impact do these activities have on individual freedom? What does this mean for shaping social coexistence? And what consequences do these developments have for the democratic system? The claim to grant citizens equal freedoms is an essential component of democracy. This enables people to work together, since everyone can assume that they do not have to fear for their place in society. Social networks and their dynamics are increasingly calling this essential requirement into question: The user-specific presentation of content creates different horizons of experience. The phenomenon of the filter bubble is referred to with concern in this context. The term describes the situation in which users no longer participate in the opinions and experiences of others and thus distance themselves from one another. Another fear is that when these different horizons of experience collide, members of society no longer succeed in exchanging ideas with one another. Rather, a deep irritation and speechlessness is to be expected (filter clash). That this is not a bad premonition was evident at the beginning of 2021, when increasingly hardened fronts could be observed in disputes in the wake of the 2020 U.S. election, with participants facing each other aggressively. This development poses a threat to freedom in that members of society are increasingly given the feeling that they have to fight for and defend their own views and opinions. This can be impressively demonstrated not least by the storming of the Capitol on January 6. In this situation, it was no longer possible to exchange views and develop common solutions based on fundamentally shared knowledge. This ultimately endangers the democratic order, since social connectedness is increasingly lacking and thus trust that cooperation is possible cannot be readily assumed. To consider the issues raised, I will link different disciplines (including computer science, media studies) and, in particular, illuminate the situation from the perspective of political philosophy – especially in the context of John Rawls’ theory.

26/05 ROAR HØSTAKER

Professor of Sociology, Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences

2020 Fellow, Nantes Institute for Advanced Study

Including or Excluding Context – from the Information Crisis to Natural Language Processing

A common thread in the debates over the digital age, since its inception in the 1940s, is the question whether information must have a meaning or not. Or, whether a text depends on its context or not. Both meaning and context are at times kept away from being relevant topics in these debates, but they somehow come back again. From the controversies between librarians and documentalists in the 1950s, to mass-digitization of books and the contemporary controversy over the sources for the datasets in Natural Language Processing (NLP). The talk shall look into some of these debates in order to show how and why the question of context and meaning tends to return.

30/06 JENNIFER GUILIANO

Associate Professor, Department of History, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis, USA

2022 Fellow, Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities, University of Edinburgh

Decolonizing Knowledge Production through Linked Open Data

A hallmark of the North American colonial process was the production and dissemination of knowledge about Indigenous peoples through the journals and records of colonizers. The violent and virulent practices that led to widespread disease, genocide, trauma and displacement in the Americas were bolstered by data collection and distribution that relied upon physical death and cultural destruction of Indigenous peoples. Equally as damaging were 20th century preservation efforts by non-Indigenous peoples that form the core of most cultural heritage collections. Analog archival collections about Native American, First Nations and Indigenous peoples were constructed through “salvage” ethnography which sought to document “disappearing” peoples. Collectors, anthropologists and historians embarked on decades-long collecting efforts that led to the extraction (forcibly and otherwise) of cultural objects, knowledge, and even physical bodies from Native communities. They created the data culture that most historians operate within as they work with indigenous materials. Historians are struggling to connect data and decolonize data practices so that they align with indigenous communities and their ways of knowing. This becomes further complicated by the fact that an overwhelming amount of historical data is held by colonial repositories and not Native communities who have different epistemological and cultural priorities.

There are general ethical and epistemological issues that researchers need to be attentive to when exposing historical materials (esp. photographs, documents and artifacts) authored by and about indigenous peoples. First and foremost, there is the issue of identity politics: who has the right to speak for/about whom and what role should non-members play in articulating a community’s history, authority or beliefs? Significantly, in colonial-centric collections, only legal access is required and/or commonly completed. Every community, every tribe, and even a single family might differ in their sense of what is appropriate for research or reuse and dissemination. When national borders divide those families, the question of research ethics becomes more complex. Can linked open data account for any of these issues or does it rely on colonial systems of knowledge production that cannot be teased apart from issues of rights and access? This presentation will highlight preliminary answers to these questions while seeking to present a vision of what a collaborative, shared authority model of Indigenous digital humanities and digital history would look like.